By Vlad Costea

The Internet is, without a doubt, one of the most groundbreaking technological innovations of the 20th century, an invention that follows the trend of globalization and political uniformization, as well as the bottomless well of information that is reminiscent of the Library of Alexandria. The concepts of a virtual world and identity have become popular in contemporary times, and using the Internet to communicate, interact with other people and download data is already a part of our daily routine. Moreover, social media has blurred the lines between our real day-to-day life and our virtual alter-ego, thus mirroring human ideas and concerns. Such a power will inevitably lead to a situation in which the users interact for social and political reasons, as in the case of the Arab Spring where political regimes fell thanks to the ease of communication and freedom of expression provided by the Internet.

Other examples where social media has influenced social movements include the 2013 protests in Turkey (that eventually led to governmental restrictions), the 2011 “Occupy Wall Street” Movement in the United States, the 2011 protests against the alleged rigged parliamentary elections in Russia, the 2013 Roșia Montană protests in Romania, and the 2012 Shifang protest in China. The consequences of these protests vary: from the ideal situation where a decision encapsulating the protesters’ views and the government’s will is made, to the scenarios where measures are taken against the protesting citizens via varying degrees of the “legitimate use of force”.

What these examples have in common is the right to use the ever-growing global inter-connected network, the Internet – a free virtual space which, regardless of its metaphysical nature, allows the users to exchange information beyond boundaries, and without which no such social and political movements would be possible. But with the existence of legislative frameworks enabling both governments and Internet companies to identify, survey, and block certain activities of the users, the equation becomes more complicated.

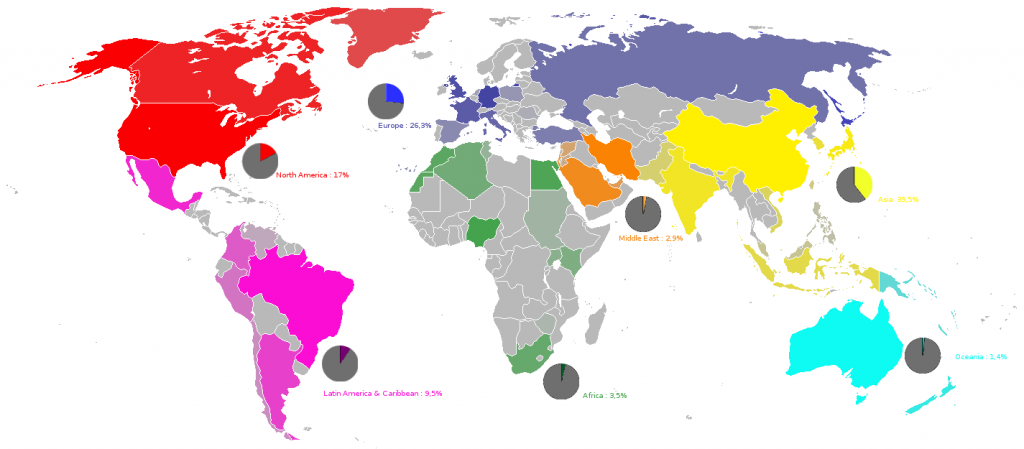

[Click to zoom] Internet users around the world, as of 2008. A darker color denotes a larger user community. Also shows the percentage of users per continent. Photo Credit: Septem Trionis, Flickr CC. License available here.

As if that were not enough, both companies and governmental agencies can store information about the users and the content they access. For example, Google provides free e-mail services but uses individuals’ personal data for commercial purposes and blocks access to certain users for infringing a certain Privacy Policy or End User Agreement; governments may block websites (as in the Chinese case), apply financial or personal freedom-endangering punishments (as in the Russian case), prohibit all the copyright-infringing materials and impose fines (as in the German case), or collect data of every user for national security purposes (as made famous by the Edward Snowden leaks of the NSA – a situation applicable to many states around the world).

In a nutshell, if a social media company wants to delete a protest page that infringes its terms and policies, it may do so, whilst also storing all the information about the activities. Governments may also have collaboration protocols with the Internet and communication companies, to the extent that the polity’s agenda is fulfilled. None of the above-mentioned social movements would have been so widespread without the aid of the Internet media. And without a framework that allows ideas to flow freely from a peer to another, their impact would be severely compromised.

Thus, an essential element in the process is Internet privacy – which shall be defined as freedom of expression that suffers no third-party interference in terms of content, and can maintain a certain extent of secrecy and anonymity (just like when sending a letter to a friend). This principle of privacy is rooted in the United Nations’ “Universal Declaration of Human Rights”, as Article 12 states that “No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.”. However, there is no international law to regulate Internet access and interference of third parties (companies or governments), yet a 2012 resolution of the UNHRC(L13) presents a “mirroring principle” between the individual and the virtual avatar:

“1. Affirms that the same rights that people have offline must also be protected online, in particular freedom of expression, which is applicable regardless of frontiers and through any media of one’s choice, in accordance with articles 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; [and]

- Recognizes the global and open nature of the Internet as a driving force in accelerating progress towards development in its various forms; … . (20/L13… The Promotion, Protection and Enjoyment of Human Rights on the Internet, supra.)”

Therefore, if there is a real-life right to privacy, then there has to exist one to protect the same information in the digital stratum. In fact, United Nations Special Rapporteur, Frank De La Rue, has written an extensive report to strengthen the claim that there is an inter-linkage between privacy and freedom of expression.

Apart from this theoretical framework on privacy and how the efforts to enforce it as a potential component of international law can serve in the analysis of the individual cases, there is also a tool that presents how free the Internet is. Freedom House’s annual report, entitled “Freedom of the Net”, takes a look at 60 countries from 6 geographical regions and presents how the Internet is blocked or censored. The states will receive the “Free”, “Partially Free” or “Not Free” label according to 10 well-defined criteria that come in the form of governmental practices:

- Blocking/Filtering websites

- Cyber attacks against regime critics

- New laws and arrests for political, religious, or social speech online

- Paid governmental commentators who manipulate online discussions

- Physical attacks and murder

- Surveillance

- Takedown requests and forced deletion content

- Blanket blocking of social media and other ICT platforms

- Holding intermediaries liable (e.g. Internet service providers, website hosts, moderators)

- Throttling or shutting down Internet and mobile services

It should be noted that the report only concerns the actions of the governments, and does not take into account what the Internet companies do – except when the decisions were made by governments, and the companies were obliged to comply.

In the contemporary context, there is much talk about how the Internet should be regulated so that governmental, corporate, and individual interests are secured – the so-called multi-stakeholder approach. Nevertheless, the treaties that emerged – such as ACTA, SOPA, PIPA, and CISPA – did not manage to balance all interests, and were usually dismissed by the end users themselves. Furthermore, such acts are perpetually drafted and brought up for debates in national legislative assemblies, with strong corporate support. Usually, political representatives themselves are technologically-challenged and cannot understand the complexity of consequences that may result from the ratification such a bill. That is why users have to remember that they are the most important part of the very Polybius-like triangular relation and channel Rousseau’s “volonté générale” whenever they have to get together to oppose legislative processes that go against their will.

Though the future of the Internet is uncertain and the rules of the game are still being written, it is clear that for as long as interests diverge and the principles of deliberative democracy are being applied, no radical changes are to take place. Nevertheless, one can easily see that there is no conservative or predictable pattern to be followed and, as the technology evolves, Internet companies and governments gain more leverage. That is why users should be aware of their rights, reaffirm them, and make sure that they are being respected on every occasion. Otherwise, history might repeat itself and combine the burning of the Library of Alexandria with the complete control of the totalitarian police state, and produce an entirely undesirable scenario.

Featured Image Credit: Frits Ahlefeldt-Laurvig, Flickr CC. License available here.