On 21 March 2021, Italian Foreign Minister Luigi di Maio flew to Tripoli, Libya to meet the interim president of the Libyan Government of National Unity (GNU). He was the first high-ranking European official to meet with the newly unified leadership of Libya after ten years of war between the rival western and eastern factions. With him in his government aircraft was Claudio Descalzi, CEO of ENI, Italy’s largest oil and gas company. The two Italians held an unscheduled summit with President Abdulhamid Dabaiba and Minister of Oil Mohamed Oun on strengthening Italo-Libyan cooperation.

For Descalzi, a veteran of oil extraction in Africa, this was the fifth official meeting with the Tripoli-based western Libyan government since becoming ENI CEO in 2016. “Claudio”, stated the GNU press release, “has expressed his maximum commitment towards investing in Libya’s renewable energies and supporting domestic demand.” For Di Maio this is only the third visit in the country.. The experience gap between the Foreign Minister and the veteran CEO should not surprise anyone. It rather reflects the Foreign Ministry’s lack of vision and long-term strategy towards the Libyan conflict, in contrast with ENI’s close relationship with the Tripoli administration.

While civil war raged in Libya, ENI kept pumping oil and making deals with the powerful Tripoli-based National Oil Corporation (NOC). Italian journalists Andrea Greco and Giuseppe Oddo have referred to the company as a ‘state within the state’ for its ability to shape government decisions at home and abroad. But how successful has this “state within the state” been in defending Italian national interests? And what does ENI’s presence mean for Libya today?

A state within the state

ENI’s strength in Libya is not accidental but stems from Italy’s geopolitical needs. Rome’s foreign policy in North Africa has three central objectives. The first two, migration and security, fall under the Interior Ministry and Italy’s intelligence agency AISE, with the foreign and defence ministries playing a marginal role. The third priority is energy policy, which is considered a matter of national survival. The bel paese has a substantial energy deficit and imports over 90% of its oil and gas needs. It is thus imperative to establish a continuous and secure flow of energy towards Italian shores.

Enter ENI, the company on a mission to satisfy Italian annual energy requirements. Its presence in Tripoli dates back to 1959. Much has changed since those initial years under ENI’s founder Enrico Mattei. The ‘oilman without oil’ turned ENI into a geopolitical force in the Mediterranean. His vision of a public company serving Italian interests abroad persists today, as the Treasury Department controls one-third of ENI’s shares.

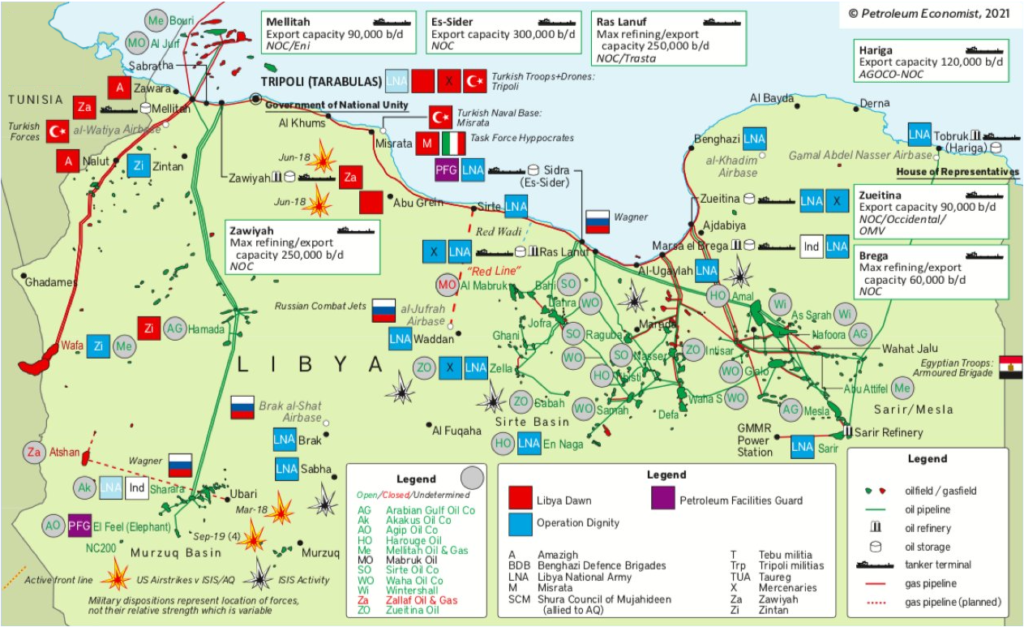

Today, the company is responsible for 45% of Libyan oil and gas production, through joint operations with the NOC which account for a sixth of ENI’s global output. Onshore, the Al Wafaa gas field and the El Feel oil deposit ensure a constant energy supply through the GreenStream pipeline, which links onshore production and the offshore Bouri field to Sicily. This 520km-long link is part of the larger Mellitah Oil & Gas complex of Mellitah and Sabratha, a joint ENI-NOC operation. ENI is also active in the Abu-Attifel field in Eastern Libya.

Since most of ENI’s activities are centred in Libya’s western region of Tripolitania, the region with the least oil and gas, the geographical distribution of its activity is almost paradoxical. However, it is precisely the oil scarcity in Tripolitania that ensures ENI’s hegemony in Tripoli. Had ENI based its operation in the oil-rich Cyrenaica region, it would not have a regional monopoly on energy production. Western Libya also hosts the only two bodies authorised to supervise energy concessions in the country: the NOC and the Central Bank.

Thus, because of ENI’s overwhelming presence in the region and because Libya’s key energy institutions are based in Tripoli, Italian foreign policy naturally favoured the western Government of National Accord (GNA) when the Second Libyan Civil War broke out against the eastern factions in 2014.

Thriving in Chaos

Despite the outspoken admission by former Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi that ENI is “a fundamental piece of our national energy policy, foreign policy and intelligence policy,” the Italian government has not always defended its strategic interests in Libya.

In 2016, Italian policymakers toyed with the idea of a military intervention to secure ENI-NOC facilities against Daesh. However, in the end they only sent the small Task Force Hippocrates to the north-western coastal town of Misrata. Similarly, the Italian Navy started patrolling ENI’s offshore facilities only after the December 2020 Turkish manoeuvres against an Italian oil rig in Cypriot water. The second failed opportunity for Italian foreign policy came in 2019 when the eastern faction’s general Khalifa Haftar started his offensive campaign, nicknamed Operation Dignity, against the GNA. Despite a frantic call for help by GNA Prime Minister Al Sarraj through an interview in the Corriere Della Sera, Italy opted for a policy of equidistanza. This attempt to start talks with eastern strongman Haftar and present Italy as above the conflict, led to Al Sarraj turning elsewhere for help and resorting to Turkish support. In a bid to expand its Mediterranean influence, Ankara did what Italy couldn’t, and sent both military aid and mercenaries to Tripoli in June 2020.

While Italy avoided direct involvement in the region, ENI continued building its presence. In 2017, amid the civil war, the company’s oil production peaked at 384,000 barrels per day. By the following year, the company acquired a 42% stake in BP’s contracts in the region. The Oil Giant expanded gas extraction by strengthening the Wafa field on the Algerian border and upgrading the Mellitah Oil & Gas complex. At the height of Operation Dignity, ENI had to evacuate its Tripoli offices. However, managers continued to fly into Tripoli from Malta, and the Chief Executive remained in close contact with Prime Minister Al Sarraj. “We are still first in Libya and Egypt,” claimed Descalzi in a 2016 press release as Haftar’s forces advanced towards Tripoli. “Where others use politics, we use technology and innovation.” While Italy negotiated with Haftar and his Libyan National Army (LNA), ENI refused to leave its western partners in the GNU, even when the civil war seemed lost.

The price to pay

How did ENI secure its operations in such an unstable context? According to a report by French think tank Ifri it did so through a ‘molecule approach’. With the support of the AISE network in the region, the company struck deals with local actors. In tandem with NOC, ENI outsourced security tasks to powerful militias in the north and tribes in the south. Tribal agreements in Fezzan in the south, where the El Feel oilfield is located, were reached through various conferences under the aegis of the Rome-based Catholic association Sant’Egidio Community. Northern deals were far more controversial. The Anas al-Dabbashi militia, responsible for protecting the Mellitah complex, and the Al-Nasr militia, in charge of security operations for the Zawiya refinery, were both targeted by UN Security Council sanctions for human trafficking and fuel smuggling.

ENI stood alone, with only the GNA as an ally. Given Italian reluctance to intervene beyond targeted secret services intervention, this was the only survival strategy. However, the cost was high. Despite support from the GNA-loyalist Sebha Military Group and air support from Misrata, the El Feel oilfield was captured by Haftar in spring 2019. A last-ditch trip to Libya by AISE vice-director Giovanni Caravelli in February of the same year was not enough to protect southern fields. Nor was the equidistanza policy effective in protecting ENI’s interest in the east, as Haftar’s January 2020 oil blockade shut down the Bu Attifel field. Only the Mellitah complex kept pumping oil and gas. The following summer, LNA airstrikes hit ENI oil deposits in Tajoura. Security guards from the northwestern coastal town of Zwara also attacked the Mellitah refinery, demanding additional compensation. ENI maintained its foothold in Libya but paid a high price: its production in the country halved from 2018 to 2020.

Future prospects

What does the future hold for Italy and ENI in Libya? The prospects are still bright. After the failure of equidistanza policies, which left a vacuum for Turkish intervention, the Italian government has been the first European delegation to visit the newly appointed GNU President. Only time will tell whether this move represents a sign of renewed Italian interest in Libya or a clumsy attempt to support ENI. In the larger context, Italian failures in Libya mirror a lack of direction of the country’s Mediterranean foreign policy strategy, marked by faux pas and tensions with neighbouring France. Yet, an olive branch could arrive from the Elysée. Despite its support for Haftar, Paris appears ready to cooperate again with Italy through Macron’s Pax Mediterranea strategy that paves the way for joint European action in the Mediterranean.

What about ENI? Beyond oil and gas exports, ENI provides 70% of Libyan energy requirements. “We never left Libya, because if we did so, the country would shut down,” argued Descalzi in a 2016 interview to Italian newspaper Avvenire. Recent showdowns between the eastern and western factions have left the national electric grid on the verge of collapse. Tripoli thus needs ENI’s technology and know-how more than ever before. On the international front, the Italian company has signed deals with the Emirati company ADNOC and moved towards greater cooperation with Total in Algeria and Cyprus. However, foreign competition remains strong in the region. Russian Wagner forces are digging trenches from Sirte to the Juafra airbase. Their goal: to establish a new oil and gas pipeline in eastern Libya. In the west, Turkish holding company Karadeniz made a bid last June to take over Tripolitania’s domestic energy market and restart infrastructural projects.

Enduring through Gaddafi’s rule, his fall, and the ensuing civil wars, ENI has proven efficient in protecting Italy’s national interest. However, its resilience in the region should not be mistaken for Italian foreign policy success. Rome’s lack of long-term strategy in the Mediterranean has left much to desire. With a new chapter of the Libyan story on the horizon, the buck now passes to Italy’s new prime minister, Mario Draghi. Will the country support its national champion in Libya in these uncertain times, or will it leave ENI to deal with Italian energy supply on its own once more?