By Linh Tran Huy

We all have our habits. Some people walk their dog. Others turn the light on and off five times before going to bed. Myself, I do periodically enjoy clicking on my bookmarks and reading the world news, just to check whether or not there has been any progress concerning the ongoing conflicts or issues plaguing this dear Mother Earth. More often than not, this will result in me finding hundreds of statistics, forecasts, accompanied by ridiculous predictions made by apparently famous scholars whom I have never heard of.

No, Europe will not make it. Yes, China will surpass the US by 2030. Nope, Obama will not wait for UN approval to launch some good old cruise missiles in Syria.

There truly is nothing more wonderful than writing off opinions as facts and disguising them under statistics and absolute statements while ignoring the other factors that could end up proving one wrong. Though to be fair, it is an analyst’s job to predict outcomes in order to warn us. The problem, however, is the following: things never happen as expected.

Once upon a time, it was believed that all the swans in the world were white: it seemed natural to think so, as nobody had ever seen a swan colored differently before. But in 1697, a Dutch explorer came to discover a black swan in Australia, thus shattering all previously established opinions. In other words, it was what American scholar Nassim Taleb calls in the field of international relations a “Black Swan event”.

A Black Swan event has three defining traits: 1. It is extremely rare, 2. Its impact on the world is considerable, and 3. It is absolutely unexpected. This phenomenon turns predictions upside-down and ridicules facts that we would take for granted. What do I mean by this? Let us look at three examples of history-changing Black Swan events.

Let us start with the end of the Cold War. At the time, experts and CIA members alike believed that this bipolar conflict would continue for decades to come. After all, it had already lasted over forty years: what were the chances of one side collapsing right now? True, living à la Soviet was tough, but it seemed stable, else the USSR would not even have been considered a superpower to begin with. Citizens had a job, could work and survive, women had access to many positions (roughly 75% of Soviet doctors were women), and progress was going forth: space programs, Sputnik, computer systems, you name it. There were weak points to the system, but that did not necessarily mean that it would collapse. Yet it did – and brutally so. Today the reasons for its failure are glaring. “Communism just did not work,” scholars would agree. However, these are but retrospective analyses, and no forecasts or pie charts helped predicting the end of the Cold War at the time.

Another event: the 9/11 attacks. The World Trade Center, the Twin Towers crashing down, 3000 killed and a war “on terror” beginning. While Al Qaeda did emerge in the 90s and that the US did see it as a threat, it certainly did not expect the extent to which the terrorist organization was willing to go to. Nobody would have expected the Clash of Civilizations to be read by Osama bin Laden, nor would we have expected the latter to actually believe in it and indoctrinate the youth into fighting to the death for the sake of the Jihad and what he believed to be the best for Islam. As a result, planes crashed, victims were had, patriotism shook up the entire country and interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq followed.

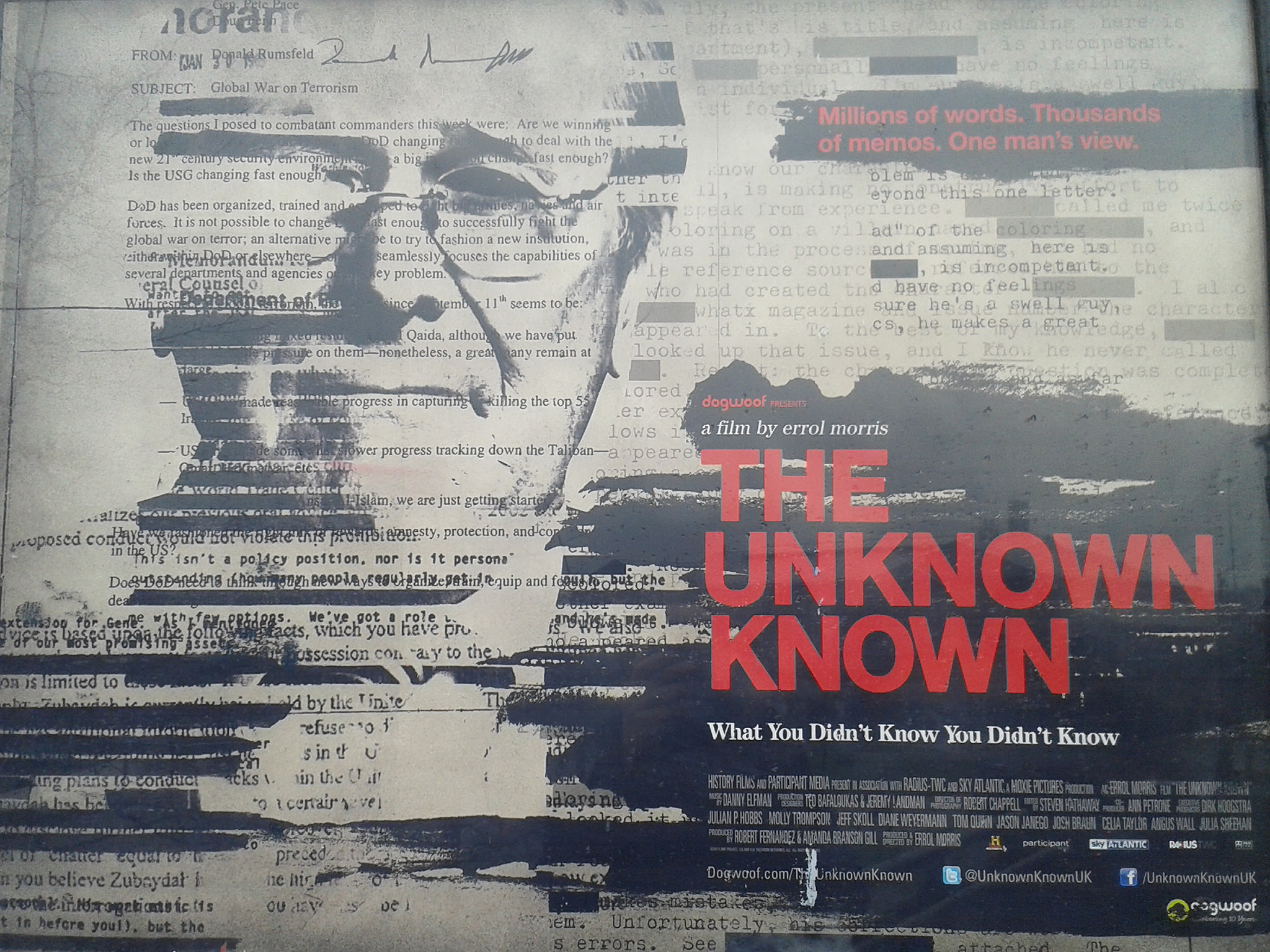

Donald Rumsfeld, Photo Credit: Gage Skidmore, Flickr CC

Let us end with one last episode: the Arab Spring. While one could explain the upheaval of the people as a fight against the authoritarian regimes in place, the fact that they were authoritarian in the place rendered the task difficult, and no one expected the event to occur at the exact moment it did, December 2010, where Muhammad Bouazizi would immolate himself to protest and thus spark the Jasmine Revolution, creating a wave of protests in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya among many others for democracy.

These Black Swan events come and go, unpredictably, cruelly even, challenging the world and the way it is supposed to function, turning tables around. They are like the school bully who has come to beat up the ace of the class expecting the year to go smoothly because nobody should hit someone with glasses. But little would the kid know that a bully does not care much for ethics. What I mean by that is that unexpected events occur because of unknown factors, the ones left out of the equation.

Now, this is not necessarily bad. Ignoring variables and simplifying things is the key when trying to make an understandable map, diagram, or explaining a theory. Yes, simple is best when illustrating a theory. But it is the worst when attempting to predict reality. That is why analysts try to insert as many existing factors as possible in order to give an approximate version of the future. But no matter how hard one tries, a few unaccounted details will be amiss, and more often than not, they will change the situation around. Gorbachev symbolized change, of the kind the USSR seemed to need, and his policies appeared to lead the Soviet Union in the right direction. Yet, behind this façade was a state ready to crumble as reforms such as the Perestroika went on. To take another example, nobody knew that on a certain day, authorities would come to Bouazizi, forbid him to make a living by selling wares, harass him and spit on him. Nobody knew that he would go to the city office to complain about his rights being abused and that the governor would simply choose not to see or listen to him. Finally, nobody expected Bouazizi to set himself on fire in the middle of the streets at exactly 11:30 am, that the accident would be reported all over the Internet, sparking trouble. Or, coming back to 9/11, no one realized that the US-supported autocracies in the Middle East would produce so much poverty and lack of education that the youth would, in the end, be easily influenced by an extremist who had read too much Huntington.

Call it a lack of foresight, an error in calculations, or an undeterminable variable. Something will always be amiss when trying to predict what will happen. This is why I frown when every paper I read asserts that the Western world is collapsing and that China will soon rule over the US. We see the facts: population, productivity, incredible economic growth, rapid industrialization and modernization in a very short lapse of time, and an indispensable export-based economy. But, what’s left out are the other factors: that such growth will slow down because of diminishing returns, that being too export-focused means putting all the eggs in one basket, that the region is too heterogeneous, or that, better, power today is not just decided in terms of economics. Let it sink in that the US is responsible for 40% of the world research and development, 50% of the world publications and citations, that almost all research published by China is derived from the US, that 8 of the top 10 universities in the world are American compared to 3 in the top 50 for China, and that the most important international institutions today (IMF, UN) are run by Western powers and ideas, and we can say that the future is not necessarily what economics and analysts make it out to be.

The point of this is not to say that predictions are useless and that scientists should go home with their tail between their legs. Far from it. Forecasting is a useful skill. However, it is not an absolute one. Facts are often not what they seem to be, because they are the product of erroneous conclusions drawn from erroneous and/or missing variables. One may hear that the US-Iran tensions could escalate into a war, that North Korea is but a joke of a threat, or that it is a menace to be reckoned with. But these people will be wrong. You will be wrong, I will be wrong. Both sides, any side. When reading shocking news, do not gasp: take it with a grain of salt, because chances are that a Black Swan event will take place and destroy any continuity one may have hoped to have.

“There are known knowns; there are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns; that is to say, there are things that we now know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns – there are things we do not know we don’t know.”

Thank you, Mr. Rumsfeld.

Featured Image Credit: Duncan Hall, Flickr CC. License available here.