by Charlotte Gardes

On October 3, 2016, British Prime Minister Theresa May set the ball rolling for Brexit: the United Kingdom will trigger article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty of the European Union by the end of March 2017 in order to start the formal departure process.

This unprecedented departure from the 28-nation bloc leaves the status of Great Britain’s trade agreements and political treaties unclear. Political and economic implications are subject to much speculation, and different options have been flagged as potential alternatives for a future relationship between the United Kingdom and the European Union: whether it can enter the European Free Trade Association and join the European Economic Area, or stay removed from the continent and become a full third-party nation (it would have to negotiate a free-trade agreement with the EU or trade on the World Trade Organization’s MFN basis).

The future of the financial sector is particularly uncertain. Whereas Great Britain used to be a manufacturing powerhouse, today it occupies a unique position in selling financial services. The financial sector makes up slightly more than 7% of UK GDP, employs more than one million people and exports about a third of its financial services to the EU. London is undoubtedly one of the most important hubs for financial services worldwide. Many financial institutions establish themselves in the UK to access both the British and European markets. London remains the dominant European location for managing trades that large companies use as a mean of protection against adverse currency or interest rate moves.

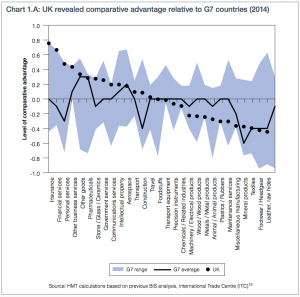

UK revealed comparative advantage relative to G7 countries (as of 2014): insurance and financial services are crucial assets.

Source: “HM Treasury analysis: the long-term economic impact of EU membership and the alternatives”, April 2016.

The European Union has launched a series of regulatory initiatives to ensure a thorough integration of EU financial markets, leading to a single rulebook of common roles for the banking, insurance and investments sectors. Since 1999, and at a steadier pace following the 2012 Liikanen report (which recommended actions in banking resolution, control and governance), a number of directives have been put in place to create a single market and enable financial services firms authorized in one member state to carry on business in another. Among them, the Financial Services Action Plan directives (MiFID, Market Abuse, Prospectus, Transparency), but also the Bank Recovery and Resolution (BRRD) and Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) directives.

The UK’s decision to leave the EU thus raises substantial uncertainty for the financial services sector. What impact will Brexit have on the UK and EU financial industries? Will financial regulation radically change under Brexit?

EU membership and UK financial services

The UK’s “financial passport” has helped to make London a leader in the financial services sector.This “passport” serves as an agreement with EU member states, allowing any firm in one EU member state to sell financial services to customers in others. As a result, UK banks, asset managers and insurance companies have enjoyed the right to sell their services freely across the EU. Europe-based firms have likewise enjoyed unfettered access to the UK. This relationship has turned London into a regional and global finance centre, providing wholesale services to the European financial sector and the wider economy. It covers derivatives, foreign currency exchanges, private and public bonds, equities and commodity trading.

Under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID) passport system, the uniformity of regulatory laws across the EU allows US-based firms, such as Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan, to interact with 30 countries across the EEA all while only having an office in London: they no longer need to comply with each member state’s specific regulation but only with the European one. These directives also specify the home and host state regulators’ responsibilities in relation to supervisory activities and resolution planning.

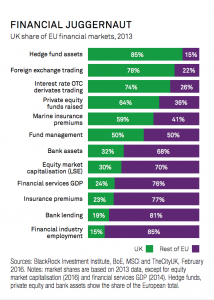

In a study for the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel, author Dirk Schoenmaker points out that findings on wholesale banking and trading are indicative in terms of London’s attractiveness as an international financial centre: nearly 50% of the total UK banking system relates to wholesale banking in London, covering trading and derivative activities that take place in several currencies (Dollar, Euro and Sterling). 70% of euro-denominated over-the-counter interest rate derivatives are traded in London.

UK share of EU financial markets (as of 2013)

Source: BlackRock Investment Institute, “Brexit: Big Risk, Little Reward”, February 2016

What impact will Brexit have on regulated firms in the UK?

The Financial Conduct Authority, the UK’s financial regulatory body, stressed an important Brexit-shaped regulatory challenge the day after the referendum: given that much financial regulation currently applicable in the UK derives from EU legislation, Brexit’s long-term impact on the overall financial regulatory framework will depend on the future of the UK’s relationship with the EU.

In addition to market uncertainty and volatility, Brexit causes critical regulatory challenges. Replicating over 40 years of EU regulations presents a very difficult task. The UK would have to incorporate all existing EU legislation into British law (the so-called “Great Repeal Bill,” promised by Theresa May at the beginning of October) in order to provide legal certainty to businesses. If the UK chose not to replicate new EU legislation, it would have to enter into negotiation with the EU every time there was an update to EU financial regulations.

In order to not lose access to the remaining 27 member states of the EU, foreign financial-services companies based in the UK would have to comply with rules equivalent to those in the EU. Such rules include the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive 2011/61/EU and the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive II (coming into force in January 2018 and covering everything from derivatives trading to bond pricing). Moreover, it would also have to implement new practical and legal barriers. Finally, they would have to obtain a separate license from each EU country in order to provide their services to European clients: a potential loss of passporting rights is one of the most challenging aspects of the post-Brexit regulatory framework.

Regarding the euro-denominated derivatives market, splitting the market and moving the swaps clearing business would require thousands of derivative contracts to be rewritten. The European Central Bank might seek to limit euro clearing and settlements under the location requirement for euro clearing houses: financial activities that rely on these mechanisms are at great risk.

For these reasons, London may no longer serve as an entry point to other European markets. That is why other European cities, such as Paris and Frankfurt, home to the European Central Bank, are, as The Wall Street Journal recently put it, battling “for London’s finance crown” (The Wall Street Journal, 1 July 2016).

But another thorn in the foot for the EU with a potential Brexit is the future of the Capital Markets Union: the European commissioner in charge of financial services policy, Valdis Dombrovskis, stated last September that the “perspective of the largest EU capital market actually leaving the EU makes this work even more urgent”.

Brexit and the Capital Markets Union

The Capital Markets Union (CMU) is a major element of the European Commission’s strategy to support jobs, growth and investment, as well as a building block of President of the Commission Jean-Claude Juncker’s investment plan. The implementation of the CMU is now another challenge that the European Union will have to face in dealing with Brexit, given the important role that the UK played in helping develop the initiative. It aims to diversify and amplify funding options available to companies by reducing existing barriers to cross-border investment in the EU and the over-reliance on bank lending. It would also reset the post-crisis regulatory framework governing European capital markets. As a combination of regulation, supervision, enforcement and market-led responses proposed between now and 2019 to withdraw all existing barriers that are blocking cross-border investments in the EU, it would allow for better risk sharing across the Eurozone and, along with the Banking Union, reduce the need for taxpayer money to absorb potential shocks.

Jonathan Hill’s resignation in the wake of the Brexit vote is an illustration of the potential disruption lying ahead, especially as the UK is likely to lose some of its influence. Yet, given the interconnectedness of UK and EU capital markets, the CMU should remain politically important and proposed reforms would prove useful either way.

However, potentially increases in financial regulation affecting insurance companies may discourage investment in securitization products, while the implementation of the CMU will add an additional layer of complexity, prolonging years of regulatory uncertainty.

What lies ahead for financial regulation in the EU?

The UK played an influential role in shaping the EU’s regulatory laws of financial services. As such, it is most likely that post-Brexit financial regulations will not significantly differ from what the UK has operated under as an EU member. Nonetheless, the future of the financial sector, both in the UK and the EU, remains uncertain and largely depends on the orientation that UK regulation will embrace.

In September 2016, the Commission underlined that the Council had reached an agreement on Simple, Transparent and Standardised securitisation in order to “free up capacity on banks’ balance sheets and provide investment opportunities for investors.” Securitization suffers a severely tarnished reputation in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and new issuances of private-label securitizations remain low; yet, the European Commission, along with the European Central Bank advocate for well-functioning securitization markets, as a sustainable and diversified funding alternative for businesses. Furthermore, an agreement still has to be found on the modernisation on the prospectus rules by the end of 2016, as well as on the proposal to strengthen venture capital markets and social investments.

As Karel Lannoo of the Centre for European Policy Studies in Brussels explains, “The UK could also choose to adopt a lighter touch and more flexibility in financial regulation, which would increase its attractiveness globally but would reduce the likelihood of harmonisation of regulations. It is also unlikely that the UK would follow such a path in the aftermath of the financial crisis and in light of the monitoring by the Financial Stability Board of the steps taken in compliance with the country’s G20 commitments.”

Much depends on the upcoming negotiations and arrangements to be made in Brussels in March of next year, although that date remains uncertain. What is certain, though, is that few regulatory arrangements are likely to preserve the London’s business center current leader status, at least regarding Britain-based banks’ freedom to run their business in the European Union.

London’s place as the European Union’s financial centre is not inevitable. As the European Union is increasingly moving towards a tightening of its regulatory regime, a potential Brexit means higher entry barriers for the United Kingdom to overcome in the near future: a loss of its “financial passport”, combined with a reevaluation of EU market access to non-EU financial companies, are great issues coming ahead. Although EU officials have constantly pointed out that there is no reorientation of financial policy in light of Brexit, a growing clash of interest is progressively taking place between the EU and the UK in terms of financial regulation.