by Henry O’Connell

Memories of Singapore’s colonial history are easily evoked when one lives in Singapore. The colonial buildings that line the historical districts, the “black and white” houses built for the 19th century colonial administrators, and the continued use of English as the lingua franca all exemplify the vestiges that Singapore has retained of its pre-independence history. If not enjoying a game of mahjong or a sojourn at their respective clubs, expatriates and locals alike continue to spend many humid and monsoonal afternoons sitting under the fanned (and now air conditioned) terraces, sipping teas, lassis or cocktails. Yet, underpinning these elements of Singaporean society, lie one of the lesser known relics of this bygone time. The wealthy’s continued reliance on domestic workers or maids to clean their homes, look after their children and cook them meals is as reminiscent as ever of Singapore’s colonial past. Distressingly, the conditions under which these domestic helpers work have evolved very little since the city state first became a British colony almost two centuries ago.

With a wealthy domestic population and a healthy share of expatriate workers, Singapore is an attractive market for people from countries such as Indonesia, the Philippines and Myanmar, who provide the lion’s share of Singapore’s domestic workers. Likewise, Singapore offers stronger institutional checks and balances relative to other countries such as the UAE, Qatar and Saudi Arabia (who also make extensive use of domestic workers) meaning that the rights of domestic helpers are better protected here. As a result, roughly 4% of the country’s population are now domestic workings, increasing from approximately 5000 in the late 1970s to over 200,000 today.

While this burgeoning population of domestic workers has helped cater to Singapore’s increasingly affluent citizens and expatriate families, the necessary improvement in working conditions and societal attitudes towards domestic workers has not kept pace.

For example, as of this year, workers from the Phillipines and Indonesia were required to be paid a minimum wage of only SGD$550 (USD$400) per month. While accommodation is usually paid for by employers, food is not always included. This wage compares to an average of SGD$4,000 (USD$2,900) for Singaporean residents, and is extremely low considering that Singapore is among one of the most expensive countries in the world.

More concerning are the working hours that domestic workers are expected to work to earn this amount. Only in 2013 did the Singapore government introduce a law requiring employers of foreign domestic workers to provide for either a minimum of one day of rest per week or a full day’s compensation. However, reports suggest that most employers prefer to compensate their maids instead, forcing them to invariably work 7 days a week, often for upwards of 16 hours per day. Only 40% of workers receive a day off each week. This reluctance to give rest days and free time is largely driven by fears that maids will get up to no good in their time off, and in a worse case scenario, get pregnant: every employer’s worst nightmare. Maids are prohibited from getting pregnant or giving birth, with unplanned pregnancies therefore leading to the termination of their work permits. This can force the roughly 100 maids who get pregnant every year to adopt drastic measures, including using unsupervised abortions, to protect their jobs and allow them to continue to send remittances back home to their families.

Added to the deplorable working conditions that maids face are the myriad forms of psychological, physical and sexual abuse that maids are frequently forced to endure. A study by the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (HOME), a Singaporean NGO working to help protect the rights of foreign domestic workers, found that 24% of maids in Singapore have poor mental health, 50% have faced verbal abuse and 6% have been sexually abused by their employers.

This abuse can extend to more extreme forms, as in July 2016, when a Singaporean mother and daughter murdered their Burmese maid, after she had been repeatedly assaulted by the father. The vulnerability of the women working as maids in Singapore makes such abuse particularly prevalent. Maids are usually young women, outside their own countries for the first time and supporting extensive families back home. This puts considerable pressure on them to continue working, regardless of the abuse they endure. Likewise, the fact that more than two thirds of maids have their passports confiscated by their employers when they start can allow employers to blackmail maids into silence. Even where maids avoid targeted, deliberate abuse, the psychological stress of caring for young children, the elderly or the infirm on an extremely intensive basis can lead to profound mental distress. The worst manifestations of this can be seen in the six different murders committed by maids in Singapore in the last 3 years, where the domestic workers in question were each found to have suffered from profound psychological distress, linked to their working conditions or treatment.

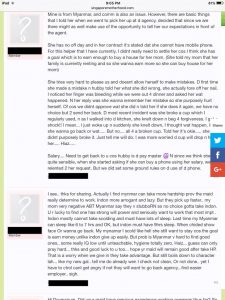

Beyond the above forms of more direct mistreatment lie the continued habit of many Singaporean and expatriate families to treat their domestic helpers with a level of disdain and negligence that lacks humanity. For example, a recent blog post shows one Singaporean criticising Indonesian maids for being lazy, sleeping too much and not working hard enough for their money, while extolling the virtues of Burmese maids because she can “scold like hell [but] she still want to stay [because] the goal is [to] earn money”. Another post asks for a view on the fairness of a 13 hour work day, with many commenting that they see no objections to having their maids work longer than that given that it is not “continuous” work and that they can have breaks in between.

Posts from various Singapore expat forums

The kind of views expressed in these forums are not necessarily held by all employers of domestic helpers in Singapore, but are nonetheless representative of many. Singaporeans and expatriates alike seem content to continue to push the boundaries of what would be considered socially acceptable in many other parts of the world, and it is difficult to imagine that they would find it justifiable to be treated in a similar manner should the situation be reversed. Expatriates who perpetuate the infringement of domestic workers’ basic dignity and rights hold a particular kind of moral responsibility here, as they enter Singaporean life and choose to adopt the lowest common denominator of standards, rather than what would be considered acceptable in their respective country of origin.

It is important to put the above in context and note that, when considered from an international perspective, maids are better treated in Singapore than in many other parts of the world, particularly when compared to the Middle East. However, this does not negate the fact that much could be done to improve the situation. To begin, laws granting domestic workers the same basic rights as Singaporeans, including a minimum entitlement to rest days and maximum working hours, would go a long way to improving the basic working conditions of many helpers. Likewise, improved access to social and mental health care for domestic workers, and particularly guaranteed access to basic services in the event of pregnancy would also help to protect workers. Employers should be prohibited from forcing maids to hand over their passports and maids should be entitled to the same freedom of movement as other Singaporean residents. Finally, mandatory sensitivity training, outlining acceptable treatment of maids, along with regular audits by government authorities to insure maids are being treated correctly, would help ensure that such workers are being treated with the respect and dignity that they deserve.